There are moments in life when the world seems to pause. You stand on a windswept cliff as waves crash far below, or under a canopy of ancient redwoods, where light filters through green in slow motion. You breathe, and something shifts — your chest expands, your thoughts quiet. In these places, you feel something larger than yourself. You feel awe. But what exactly makes a landscape feel magical? And why does our brain respond so powerfully to certain environments?

Outline

- The Nature of Awe: More Than a Feeling

- Landscapes That Stir the Soul

- How the Brain Reacts to Awe

- Why Awe Is Good for Us

- Designing for Awe: Can Magic Be Made?

- Final Thoughts

- FAQs

The Nature of Awe: More Than a Feeling

Awe is not just a poetic word. Psychologists define it as an emotional response to something vast that transcends our current understanding of the world. It often includes two components: perceived vastness and a need for cognitive accommodation — that is, the experience is so profound it challenges how we see things, requiring us to adjust our mental models.

Unlike joy or fear, awe quiets the ego. It creates a sense of smallness, not in a belittling way, but in a humbling, connecting one. It’s the feeling of being part of something greater — something ancient, grand, and unknowable.

Landscapes That Stir the Soul

Not all places are equal in their capacity to evoke awe. Certain environments repeatedly surface in studies and personal accounts: towering mountains, dense forests, star-filled skies, vast deserts, thundering waterfalls. But why?

Let’s look at some real examples:

- The Grand Canyon, with its sheer immensity and layered history written in stone, offers a direct confrontation with geological time.

- The Northern Lights, dancing across the sky in Arctic regions, feel otherworldly, shifting our perception of what’s possible in nature.

- Mount Fuji in Japan has inspired poets, painters, and pilgrims alike for centuries, a symbol of stillness and sublimity.

These landscapes are marked by contrast: vast scale, rare phenomena, unfamiliar perspectives. They exceed our expectations of what the world can look like — and that’s precisely the point.

How the Brain Reacts to Awe

Neuroscience offers fascinating insight into what awe does to our brain. Studies using fMRI scans show that awe deactivates the default mode network, a set of brain regions associated with self-referential thinking — the inner monologue of “me, me, me.” In awe, that voice quiets.

Instead, awe activates areas linked to attention, emotion, and meaning-making. It boosts activity in the prefrontal cortex, helping us process complex ideas. At the same time, the parasympathetic nervous system engages, slowing our heart rate and breathing — a physiological “pause” button.

Key reactions to awe include:

- A heightened sense of time and spaciousness

- Increased openness to new ideas

- Enhanced memory encoding

- Reduction in focus on the self

Why Awe Is Good for Us

Awe doesn’t just feel good — it is good. Research has shown it has tangible benefits for mental and physical health:

- Reduced stress levels: Awe can lower levels of cytokines, proteins linked to inflammation.

- Improved mood: Even short awe experiences can reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms.

- Boosted generosity: Awe expands our sense of connection, making us more likely to help others.

One landmark study found that people who took weekly “awe walks” — simply going outdoors with the intention to notice beauty and vastness — reported greater joy and less daily stress over time.

Remember: Awe is not reserved for grand adventures. A shaft of light through a city window or the symmetry of a leaf can hold the same magic — if we’re present enough to notice.

Designing for Awe: Can Magic Be Made?

Can we design places to create awe? Architects, urban planners, and landscape designers have long tried. Think of Gothic cathedrals, Zen gardens, or mountaintop temples — each carefully crafted to draw the eye upward, slow the body, or evoke silence.

Some principles behind awe-inspiring environments:

- Vertical scale: High ceilings, mountains, trees

- Light and shadow: Shifting light evokes mystery

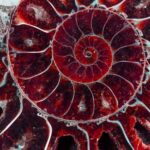

- Fractal patterns: Found in nature, pleasing to the brain

- Unexpected juxtapositions: A solitary tree in a barren desert

While not every space needs to overwhelm, incorporating elements of nature, silence, and scale can bring more awe into our everyday environments.

Final Thoughts

The feeling that a place is “magical” isn’t just romanticism — it’s biology, psychology, and centuries of human longing converging in a moment of stillness. Awe reminds us that there is more to the world — and to ourselves — than we often allow. It’s an invitation to pause, to feel, and to remember what it means to be truly alive.

FAQs

1. What causes a feeling of awe in nature?

Awe is typically triggered by vastness, beauty, and novelty — such as towering mountains, dramatic skies, or rare natural events — which challenge our understanding and require us to mentally adjust.

2. Can everyday places evoke awe?

Yes. Awe doesn’t require exotic landscapes. A moment of silence in a forest, the complexity of a spider’s web, or a powerful sunset can evoke awe if we’re attentive and open to it.

3. What is the benefit of feeling awe regularly?

Regular experiences of awe have been linked to lower stress, improved mood, greater creativity, and a stronger sense of connection to others and the world.