In the flickering light of a fire, deep within a prehistoric cave, a human hand reaches out—not to grasp, but to mark. Fingers dip into pigment, tracing images of bison, hunters, stars. These are not decorations. They are early expressions of a question that would echo through millennia: What does it mean to be here? From the silent strokes on stone walls to the humming of telescopes orbiting Earth, our species has been driven by a force as old as our breath—wonder.

Wonder is not mere curiosity. It is a yearning. A longing to connect what we see with what we don’t. A bridge between experience and meaning. This is the story of that yearning—and how it shaped the course of human thought.

Outline

- The Spark in the Cave: Where Wonder Begins

- From Myths to Models: Making Sense of the Unknown

- The Scientific Mind: Wonder as Method

- Space, Time, and the Questions That Persist

- Why Wonder Still Matters Today

- FAQs

The Spark in the Cave: Where Wonder Begins

The earliest signs of wonder are not found in words, but in symbols. In the Chauvet Cave of France, over 30,000 years ago, humans painted animals with astonishing detail and intention. Why? These weren’t survival instructions. They were attempts to understand, to remember, perhaps even to connect with something beyond the immediate world.

Anthropologists suggest these early artworks weren’t just about animals, but about patterns—the cycles of life, the rhythms of the hunt, the mysteries of the stars. Wonder, in its first form, was an attempt to make meaning of mystery.

From Myths to Models: Making Sense of the Unknown

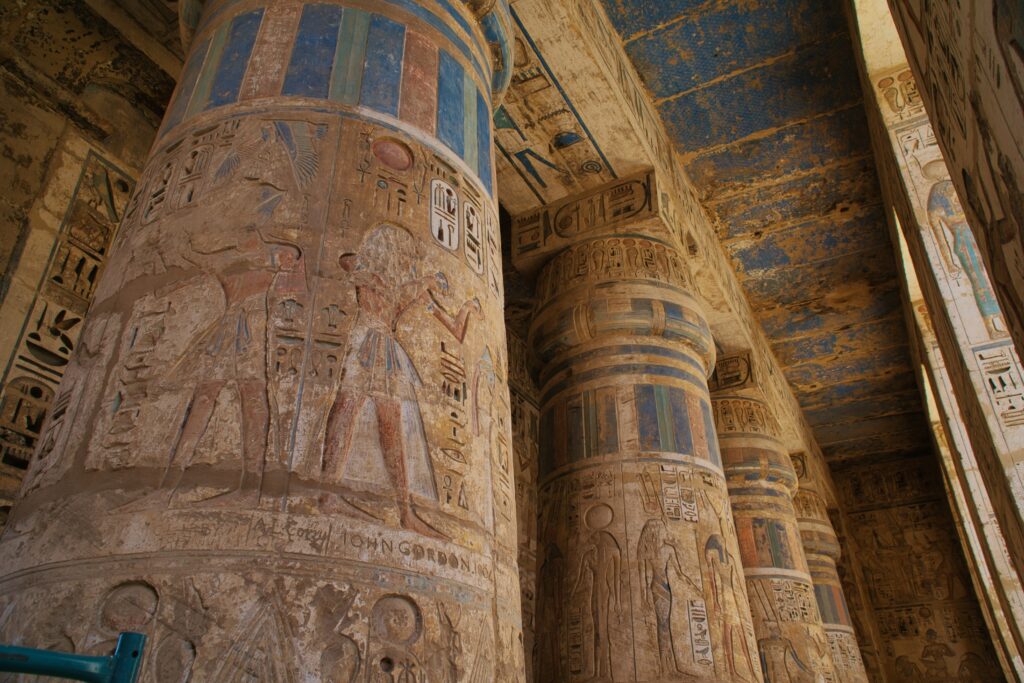

As civilizations emerged, wonder took on new shapes. The Sumerians looked to the skies and mapped constellations. The Egyptians aligned pyramids with stars. In every corner of the ancient world, humans began crafting myths—rich stories not just to explain the world, but to connect emotion, memory, and morality.

These myths were more than imagination; they were early frameworks of knowledge. Before mathematics, before physics, there was metaphor. The thunder wasn’t just noise—it was a god’s voice. The sun wasn’t just light—it was a chariot across the heavens.

But slowly, myths evolved into models. The Greeks, especially, shifted from mythos to logos—from storytelling to structured thought. Thales asked whether everything might come from water. Pythagoras saw harmony not just in music, but in the universe itself. Socrates questioned everything, famously claiming, “I know that I know nothing.”

The Scientific Mind: Wonder as Method

The Enlightenment brought a transformation. Wonder was no longer just spiritual or philosophical—it became empirical. Galileo turned his telescope toward Jupiter and saw moons orbiting it, challenging centuries of belief. Newton asked whyapples fall and uncovered the laws of gravity.

Science did not kill wonder. It organized it. The question “Why do stars shine?” no longer ended in myth, but in fusion, hydrogen, and quantum physics. Yet behind every discovery was the same fuel: a relentless need to ask.

Remember: The scientific method is simply structured wonder.

- Ask a question

- Make observations

- Form a hypothesis

- Test, refine, ask again

Wonder became cyclical—each answer opened ten new questions.

Space, Time, and the Questions That Persist

In 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope was launched into low Earth orbit. It has since captured images of galaxies so far away, their light began its journey before Earth had oceans. We now ask: What was before the Big Bang? Are we alone in the universe? What is consciousness?

These aren’t trivial curiosities. They are existential coordinates, mapping where we stand in relation to everything else.

And yet, we still gaze at the stars with the same impulse that guided cave painters: There must be more.

Why Wonder Still Matters Today

In a world of information overload, we risk losing the art of asking. Algorithms finish our questions before we’ve thought them. But wonder requires pauses. It grows in silence, in the gaps between knowing.

To wonder is to resist cynicism. To remember that knowledge is not a wall, but a door.

FAQs

1. Why do humans ask philosophical questions?

Philosophical questions arise from our ability to reflect on ourselves, our mortality, and our place in the universe—traits linked to higher consciousness, self-awareness, and abstract thinking.

2. When did humans first start asking “why” questions?

Though we can’t date the exact moment, symbolic behavior in early Homo sapiens—like cave art (30,000+ years ago)—suggests a cognitive shift toward deeper questioning and abstract thought.

3. How does wonder influence scientific discovery?

Wonder is often the starting point for scientific inquiry. Many major breakthroughs began with simple, awe-inspired questions about nature, patterns, or phenomena we couldn’t explain at the time.